Bill to Ban Asbestos Reintroduced by Oregon Legislators

Two Oregon legislators have reintroduced a bill to end the importation of asbestos, a known carcinogen banned in nearly 70 other countries. The bill would amend the Toxic Substances Control Act of 1976 and ban asbestos in the United States.

The Alan Reinstein Ban Asbestos Now Act of 2023, first introduced in 2019, was reintroduced March 30 by Sen. Jeff Merkley and U.S. Rep. Suzanne Bonamici. It would “prohibit the manufacture, processing, use and distribution in commerce of commercial asbestos and mixtures and articles containing commercial asbestos, and for other purposes,” according to the bill.

Reintroduction of this bill comes at a pivotal time as the Environmental Protection Agency considers a proposed asbestos ban.

“This long overdue legislation will stop hundreds of tons of raw asbestos imports and asbestos-containing products from entering the United States,” said Linda Reinstein, president of the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization, which she co-founded in 2004.

Reinstein’s husband Alan, the bill’s namesake, died of mesothelioma in 2006. The disease is caused by exposure to asbestos and there is no cure.

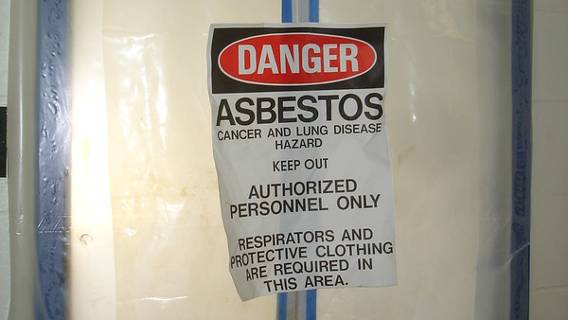

“ARBAN will protect all Americans — especially vulnerable workers, disadvantaged communities, consumers, first responders and children — who are most at risk of being exposed to this deadly carcinogen,” Reinstein said.

EPA Also Exploring Asbestos Ban

In 2022, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency proposed a ban on chrysotile asbestos. The ban would force U.S. companies, like those in the chloralkali industry, to stop using asbestos within two years.

As many as 40,000 deaths are caused by asbestos exposure each year in America, according to the American Public Health Association. Currently chrysotile asbestos, or white asbestos, is still being imported and used in the U.S. today. The chloralkali industry utilizes it to create chlorine that is then used to disinfect drinking water. Public comment on the EPA ban closed April 17.

Some companies in the chloralkali industry suggested it could take more than a decade to shift away from using white asbestos, while critics say it can be done more quickly.

EPA officials banned asbestos in 1989. However, an aggressive counterattack from the asbestos industry led the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit to overturn the ban in 1991. In addition to its use in the chloralkali industry, asbestos can still be found in aftermarket automotive brakes and linings, brake blocks, sheet gaskets and other vehicle products.

‘Asbestos Is a Silent Killer’

When Alan Reinstein was diagnosed with mesothelioma, neither he nor his wife had ever heard of the disease. He died within three years of his diagnosis. Linda Reinstein co-founded the ADAO with Doug Larkin, who’s loved one was also diagnosed with mesothelioma. Together they began their mission to end asbestos exposure and protect the public health. Larkin died in 2017 of ALS.

“Asbestos is a silent killer—a stealthy and insidious assassin that can lie dormant in homes, schools, workplaces and consumer products, only to strike when least expected,” Reinstein wrote in an email to Asbestos.com. “Exposure to even the smallest whisper of asbestos fibers poses a grave danger, as it can lead to serious and often fatal diseases, such as mesothelioma, that may not manifest for 10 to 50 years after exposure.”

Asbestos, which was once widely used in flooring, insulation and building materials, causes mesothelioma and a progressive lung disease called asbestosis. Hundreds of thousands of patients have filed asbestos lawsuits to provide compensation to cover medical bills and lost wages. Family members who have secondary exposure to asbestos may also file a legal claim.

For Reinstein, banning asbestos means one thing: saving lives.

“If we sat in grief and anger, nothing would change,” Reinstein said. “I see Alan, Bill and Doug in our work today as we fight for a toxic-free world.”