Canadian Town of Asbestos Changing Its Name for Economics

Asbestos Exposure & BansWritten by Tim Povtak | Edited By Walter Pacheco

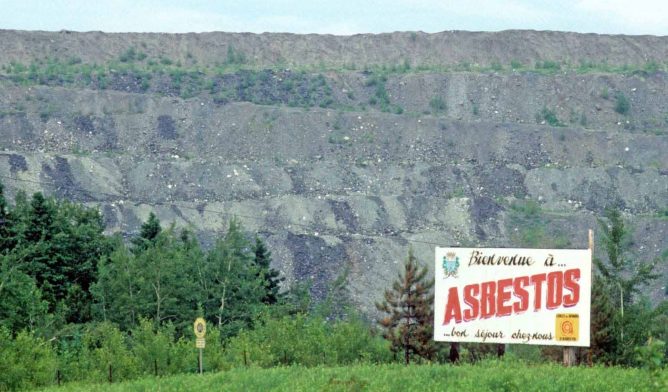

Officials in Asbestos, Quebec, have been struggling for years to develop a new identity for the small Canadian mining town.

Changing its name might do the trick.

Mayor Hugues Grimard announced recently that his town in southeastern Quebec is looking for a name change in 2020, believing it could spark a much-needed economic recovery.

The natural link between the town’s name and the toxic mineral — once so compelling — has become a roadblock to any future development. Exposure to asbestos can lead to deadly diseases, including mesothelioma cancer.

“There is really a negative perception around asbestos,” Grimard told CBC News. “We have lost many businesses that don’t want to establish themselves here because of the name.”

An Emotional Issue

The historical significance of the connection between the town and mineral is profound, making the idea of a name change an emotional issue for the 6,800 residents today.

For some, there is a history they want to preserve. For others, they want it to end.

The once-coveted mineral was mined there for more than 120 years, creating thousands of high-paying jobs that led to the town’s naming and development, shaping its identity.

The Jeffery Mine occupied one-sixth of the town’s 12 square miles. Owned and operated by Johns Manville for much of its history, it was once the largest open-pit mine in the world, providing asbestos material that fueled the construction and manufacturing industries everywhere.

It also fueled the pride that engulfed the town for a century.

Unfortunately, the asbestos also was killing thousands by causing cancers such as mesothelioma and lung cancer.

As the public became more aware of how toxic it was — and the number of people dying because of it — the demand for asbestos dropped significantly.

The word itself is offensive to some.

More than 60 countries today ban the use of the mineral completely.

The Jeffery Mine was closed in 2011. Canada finally banned asbestos in 2018. The United States closed its last mine in 2002 and severely restricts all imports.

The World Health Organization estimates that more than 100,000 people die globally each year from asbestos-related diseases.

Name Has Blocked Economic Development

Grimard said in various interviews recently that the word asbestos has prevented many businesses from investing in the area.

“Four businesses have told me they don’t want to establish here because of the name, that their investors were reluctant to invest here,” he said. “We had people here who went to Ohio recently to do economic development, and people didn’t even want to take their business cards. The perception — the media phobia — is still present in terms of asbestos.”

The town has attracted some new businesses, including a duck processing plant and a semi-trailer manufacturer, with tax incentives, but only a fraction of what it wants.

The name-change announcement that the town council and mayor had agreed to last month has been met with mixed feelings. They are encouraging townspeople to submit suggestions.

Meeting to Discuss Next Month

A special meeting to discuss the issue with residents will be held Jan. 9, 2020.

“It is in thinking of future generations that elected officials decided in favor of a name change, while knowing that it is essential to continue to highlight the history of our city, despite the name change,” the town posted on its official website.

Town officials in 2006 tried changing the name, even before the Jeffrey mine closed, but were overruled by residents. The mayor estimated it would cost $100,000 to complete the name change in 2020.

He said the name Asbestos has not been a problem for most of those who live there, but more for those who live outside the area. The mineral is known as amiante in French, which many of the residents speak.

Like many in the town of Asbestos, Grimard still believes there is a place for the safe and controlled use of asbestos.

“I’ve been a resident of Asbestos all my life. I’ve been around asbestos regularly, and I’m in perfect health,” he said. “For me, it’s really on the level of perception, in terms of commercializing of our city, that we really have a problem. If we want to modernize our territory, we owe it to ourselves to change our identity.”