Asbestos Mining Town in Canada Searches for New Identity

Asbestos Exposure & BansWritten by Matt Mauney | Edited by Walter Pacheco

Asbestos wasn’t always an ugly word.

Once hailed as a miracle fiber in manufacturing and construction, it is now scorned for its toxicity and link to mesothelioma and other deadly respiratory diseases.

Perhaps no place knows that fall from grace better than the small town of Asbestos in southeast Quebec. Not only did the asbestos industry give the Canadian mining town its name, but it also shaped its identity, economy and legacy.

The now defunct Jeffery Mine, which occupies nearly one-sixth of the town’s 12 square miles, was Canada’s largest asbestos mine and served as the town’s main employer when it shut down in 2011.

At its peak, the open-pit asbestos mine employed more than 2,000 of the town’s 7,000 residents.

Now, five years later, Asbestos is searching for a new identity and a way to rewrite its legacy.

Asbestos: Quebec’s White Gold

Canada has a long, dark history with asbestos.

Before mining stopped in 2011, the country was one of the world’s main producers of the naturally occurring carcinogenic mineral.

Mining efforts started in the 1850s, when chrysotile deposits were discovered in Thetford, Quebec. The city of Thetford Mines was founded in 1876, and it became a hub for one of the world’s largest asbestos-producing regions.

The Jeffrey Mine opened in 1879, less than 50 miles south of Thetford Mines.

By the turn of the century, the Canadian asbestos industry was booming, with Quebec leading the way.

The town of Asbestos was the site of the infamous 1949 asbestos strike, a four-month labor dispute credited for leading to the Quiet Revolution — a period of socio-political and socio-cultural change in Quebec.

The strike is regarded as one of the most violent labor disputes in Canadian history. The unions and companies eventually reached a compromise, leading to a small pay increase and slightly better conditions for roughly 5,000 asbestos miners in the Eastern Townships.

Quebec’s asbestos industry was back on track. By the 1950s, Canada’s annual mining haul exceeded 900,000 metric tons.

The industry sprouted towns like Asbestos, boosting economies and providing for thousands of families, but the cost was much greater than the reward.

As the dangers of asbestos exposure became more known, the toxic mineral was still used heavily in construction and manufacturing because of its affordability and durability. It was still considered the ideal material to use through the 1970s.

And Canada was at the forefront of production.

Manufacturers felt the benefits of using asbestos outweighed potential risks. It took decades for the Canadian government to finally commit to banning asbestos. Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau addressed the country’s asbestos epidemic in May 2016.

“We know that its impact on workers far outweighs any benefits that it might provide,” Trudeau said.

Canada no longer exports asbestos, but still imports asbestos-containing products.

Canada’s mesothelioma cancer rate is one of the highest in the world. Asbestos exposure is still the No. 1 cause of occupational death in the country. In 2012, Quebec recorded 180 new cases of mesothelioma, more than any other province.

Medical professionals don’t expect those numbers to level off anytime soon, given that mesothelioma’s latency period is 20 to 50 years.

A 2004 health report from the Institut National de Santé Publique Du Quebec compiled data from six studies that assessed the cancer risk of the population in Quebec’s asbestos mining region.

The studies suggested that there was a statistically significant increase in the incidence of asbestos-related diseases and mortality from respiratory cancers, especially among men in Asbestos and Thetford Mines.

Those health fears add to the dynamic facing towns like Asbestos. The closing of the Jeffrey Mine may have taken away jobs and the town’s identity, but the future sacrifice could prove far greater.

Legacy of Johns Manville & the Jeffrey Mine in Asbestos

Many know it as the Jeffrey Mine or the Johns Manville Mine.

But residents of Asbestos simply called it “the hole.”

Johns Manville was the mine’s corporate owner and operator for most of its history. Not only was the company the town’s largest employer, but residents relied on the company to fund activities in their everyday lives such as youth sports leagues and churches.

The open-pit mine was expanded in 1969, making it one of the largest in the world. The expansion required the adjacent town to relocate, showing the town’s symbiotic relationship with the mine.

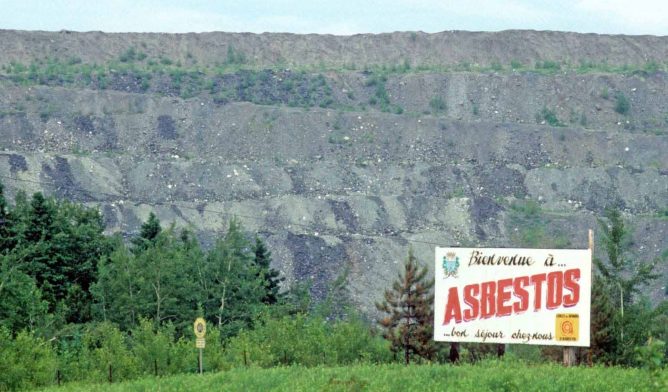

Panoramic view of the open-pit mine in Asbestos, Quebec.

However, the demand for asbestos fell significantly in the 1980s, as the medical community exposed its carcinogenic properties. Lower demand and decreasing government subsidies forced the Jeffrey Mine to operate sporadically in the 15 years prior to closing for good.

Some Consider Asbestos History a Source of Pride

When Canada’s asbestos industry came to a standstill in 2011, some residents of Asbestos were still loyal to its namesake.

In 2012, longtime Asbestos mayor Hugues Grimard told Canadian newspaper the National Post the town’s name was a “source of pride” and that changing it “would be to renounce our own identity.” He also stressed the importance of reopening the Jeffrey Mine, noting it would add 500 jobs.

“We are no sicker here than elsewhere in Quebec,” he said. “The average age confirms that.”

Historic image of workers drilling in Asbestos, Quebec.

But Grimard recently proposed a different reason for opening the mine in an August interview with The Globe and Mail, announcing the town’s revised vision of the future relied on attracting new businesses.

“There are several projects on the table, several important announcements that have been made, and others are coming,” he told the newspaper. “The strategy is working.”

At the time of Grimard’s 2012 comments, Canada’s beleaguered asbestos sector relied on a $58 million loan promised by the Quebec Liberal Party. The loan would cover more than two-thirds of the cost of renovating and reopening the Jeffrey Mine, helping it to operate for another 20 years.

But before the government transferred money to the mine, the Parti Quibecois defeated the Quebec Liberal Party in a provincial election and cancelled the loan. In its place, the government installed a $50 million regional diversification fund to support business projects.

Grimard hopes those funds will help Asbestos create a new identity and move on from the industry that supported the town for more than a century.

Crafting a New Identity in Shadow of Asbestos

Several businesses have recently found a home in the former mining town, including Moulin7 Microbrasserie, a microbrewery with an atmosphere and beers that honor the town’s past. Their lager, named Mineur (French for miner), is described as a “tribute to all miners, who were the builders of the town of Asbestos.”

Their Belgian-style Witbier, called L’Or Blanc, is named for the “white gold” or asbestos that was the basis for town’s economy for decades, while the 1949 milk stout is representative of the dark period of the 1949 asbestos strike.

The brewery’s décor is inspired by Asbestos’ industrial past, with furniture and decorations recycled and repurposed from the mills and offices of the Jeffrey Mine.

Other new businesses in the town don’t share the same homage, but they are equally important to the local economy such as a pharmaceutical company and cheese factory.

Brome Lake Ducks, the oldest farm in Canada specializing in the breeding of Peking ducks, announced plans in June to open a $30 million processing plant and hatchery in Asbestos. That project is expected to create 150 jobs over the next few years.

Preserving Asbestos’ Past & Looking into the Future

Breweries and factories are a start, but the Jeffrey Mine, while inactive, remains the town’s largest and most notable landmark. It’s hard to hide a 1,148-foot-deep pit, but the town has begun demolishing all unused buildings at the site.

Much of the mine’s past is now preserved in the Asbestos Mineral Museum, located in a section of the town’s municipal library, formerly a church. The museum features rock and mineral samples from the mine along with permanent and temporary exhibitions, video presentations and educational workshops.

A large, tabletop diorama of the town shows just how much the mine is a part of the town’s landscape.

Before 2011, the museum offered guided tours of the mine, including one with access to a then-active underground asbestos mining operation, complete with hard-hats and other appropriate gear.

Anthony Rich, an industrial hygienist and asbestos awareness advocate, made several visits to the museum during trips to Asbestos.

“During each visit, museum tour staff indicated chrysotile [asbestos] was ‘safe’ and that they were proud of the mining heritage of the region,” Rich told Asbestos.com.

The People of Asbestos Make the Place

German photojournalist Matthias Walendy traveled to Asbestos in 2014 to document the unique Canadian town.

What he found was a place that tries looking at an optimistic future, while reflecting on its past and longing for the “good old days.”

“[My perception] changed the first day I was there,” he told Asbestos.com. “It wasn’t the dirty, poor place I thought it would be. I met a lot of people, nice people. It was a town, like a suburban town, like everywhere else.”

Aerial view of the town of Asbestos, Quebec.

Walendy learned the residents of Asbestos weren’t necessarily ashamed of their past but rather desensitized from it.

“When I talked to people about their history, they thought it was wrong that they closed [the mine] but there was resignation,” he said.

He noted older residents were more reminiscent about the town’s mining past, while younger residents showed little to no interest in the history of the mine or the town.

“A lot of young people and young families never worked in the mine,” Walendy explained. “Now the fathers of these families work in nearby towns, leaving for work at 6 in the morning and getting home at 6 in the evening.”

Walendy admitted that, initially, he was nervous the residents would be aggressive toward him or fearful that he might misrepresent them.

The town and its people have been the subject of media criticism in the past. A 2011 segment from Comedy Central’s “The Daily Show” poked fun at the town, with a reporter asking a local businessman “does the word asbestos mean something different in French?”

But with Walendy, the residents and town officials were friendly and accommodating.

“When people asked me about the project, I always said I’m interested in the history and how the town has changed,” Walendy said. “There was a lot of freedom there. I talked to everyone.”

Is the Town of Asbestos Safe?

Rich visited Asbestos on three separate occasions in the past eight years. While his interactions were mostly limited to employees of the “asbestos tourism” industry, he too felt a normalcy and vibrancy about the town.

But one characteristic stood out — the huge asbestos mine tailings surrounding the town, and in some cases, right up to residents’ backyards.

Mine tailings are toxic and become extremely dangerous when disturbed. Wind can pick up asbestos fibers, leading to inhalation. Environmental asbestos exposure is a growing concern in areas where naturally occurring asbestos is present.

Environmental exposure has led to an increase in mesothelioma cases in women and younger residents, according to Quebec’s health report.

“Some parts of the mining towns were said to be built on top of the asbestos waste rock,” Rich said. “In order to find more uses of the combined hundreds of millions of metric tons of asbestos ore tailings in the region, the mining waste found its way into much of the local infrastructure.”

And like the museum staff, there are still government officials and others within Quebec’s mining territories who believe chrysotile asbestos can be mined and used safely.

Rich said a combination of the long latency period associated with asbestos exposure, propaganda by the local industry and economic factors that some feel outweigh potential risks may contribute to this mentality.

“There is much work to be done to make these former asbestos mining areas safer for residents,” Rich said. “Perhaps mass evacuation and relocation of residents from asbestos-contaminated areas may reduce exposure risks, but as one of the museum tour guides once responded to a question about the chance of moving away from the town Asbestos, ‘…don’t hold your breath.’”