20-Year Pleural Mesothelioma Survivor Is a Sugarbaker Legacy

Tim Crisler believes there is only one way to explain how he – a most unlikely candidate – became one of America’s longest living pleural mesothelioma survivors: The power of prayer.

Crisler, 66, was diagnosed 20 years ago. He received aggressive surgery that nearly killed him, chemotherapy that made him want to die, and radiation that damaged his heart.

Yet he survived it all – beating incredibly long odds – to thrive again.

“In my opinion, this isn’t just a coincidence,” he told The Mesothelioma Center at Asbestos.com. “It’s certainly not something I deserved or earned by any stretch. But God kept me alive. He healed me.”

Life-Saving Surgery Performed by Dr. David Sugarbaker

A few days before his extrapleural pneumonectomy surgery 20 years ago at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, close to 80 friends and family members gathered for a backyard prayer vigil at Crisler’s home in Kennesaw, Georgia.

The emotional gathering was led by his father-in-law, a Baptist minister who had just returned from a mission trip in Central America. Each person said a short prayer for Crisler, who was facing this cancer with no cure.

And those prayers were answered.

“When you are dying, you’ll try anything. I left for Boston thinking, ‘Maybe I don’t have to die from this,’” Crisler said. “I know that people don’t believe in God so much these days, but it happened. It’s real.”

Even his thoracic surgeon, Dr. David Sugarbaker – the biggest name in mesothelioma treatment – never imagined Crisler would survive this long.

“He just told me to get my will in order because, although he did his best, he told me I wasn’t going to last very long,” Crisler said. “He guaranteed it.”

Although their last conversation came early in 2003, Crisler lived to become one of Sugarbaker’s greatest achievements. The legendary surgeon died in 2018, leaving Crisler as part of his legacy.

Survivor Beat the Odds with No Recurrence

Pleural mesothelioma is a terminal cancer with a median survival of just over 12 months. Although some advances have been made, the five-year survival rate is still less than 10%. Even with the most effective multimodality treatments, tumors removed with surgery inevitably return with a vengeance.

Crisler, amazingly, never had any cancer recurrence. Mesothelioma cancer is gone for good, he believes. Those annual scans looking for evidence stopped 10 years ago.

He also recovered from open-heart surgery in 2007 to repair serious artery blockage that was about to cause a life-ending heart attack.

Navigating Pain Medication Regulations

Crisler’s biggest problem today – particularly over the last five years – is the residual pain that rarely subsides, stemming from the 12-hour surgery in 2002 that removed his entire left lung, parts of his heart lining and diaphragm. It also caused permanent nerve damage, which haunts him most days now.

“If you want to hear someone complain about pain, I can tell you all about that. It comes with activity now, my whole left side, where the lung was removed,” he said. “The last five years have been tough. Before then, I was good, mostly pain-free. But times have changed.”

The difference, Crisler said, is the pain medication he can no longer obtain. Until 2017, he relied heavily on fentanyl, a powerful synthetic opioid that was once considered a safe option when carefully monitored.

Fentanyl, however, became a popular recreational drug that often was mixed with heroin, causing an alarming number of overdose deaths. This led to much tighter governmental restrictions on its use.

Those stricter regulations, originally designed to lower prescription drug abuse and stop black market providers, also have pressured doctors to stop offering it to patients such as Crisler, who can benefit greatly from it.

His longtime doctor in Georgia would no longer prescribe it, referring him to another doctor who refused to see him when he told her of his interest in fentanyl.

“This has become a huge problem that people don’t want to talk about. Our government has made it impossible for me to get fentanyl at this point,” he said. “And I’m not alone in this. Older patients, especially cancer patients, are having problems because doctors can’t prescribe it with so much governmental intervention.”

Crisler said he has oxycodone and methadone available, but often doesn’t take them because of side effects and ineffectiveness. He has tried virtually everything else, but nothing has worked for him as well as fentanyl did for so many years.

“When you ask for it they think you are just a druggie. I understand, you don’t want young people getting addicted, or dying from it, but it worked for me. I was very active and did well when I had it,” he said.

Living a Better Life

For many years, Crisler was seen as a shining, post-surgery success story in the mesothelioma community. He and his family often traveled south to the Virgin Islands and Costa Rica.

He would ride his Harley-Davidson Wide Glide motorcycle to Key West, Florida, for parties. He was no angel before or after his mesothelioma diagnosis, he said.

“I partied like I was in my 20s again because I thought I wasn’t going to live very long,” Crisler said. “But after five years or so, when nothing bad happened, I started wanting to do the right thing and live a better life. And I did. I have.”

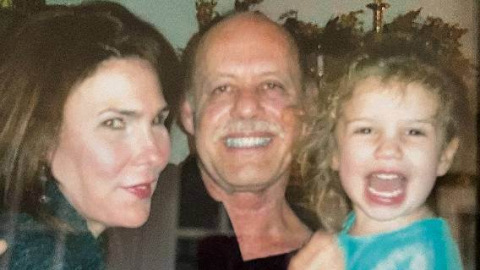

When he was first diagnosed, Crisler’s children were 19, 13 and 3. Over the last 20 years, he watched them mature into adulthood, cherishing every moment together.

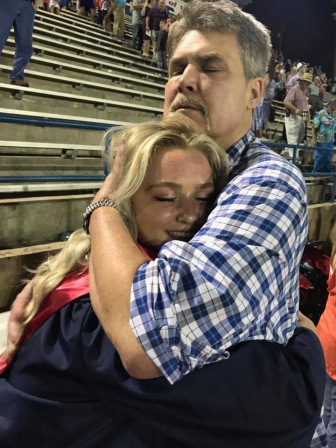

He has gone to graduation ceremonies at Kennesaw State University and the University of Georgia. Through the years he went to their ballgames, cheerleading competitions, gymnastic events, birthday parties, picnics, races, dances, festivals and everything else imaginable. They were events he never thought he would see.

“I wondered from the start, would I be around long enough for my youngest to even remember me? The children were foremost on my mind,” he said. “I wondered, who would walk my daughter down the aisle? How was my son going to handle my death? So many questions, worries and sorrows. Way too many.”

His family always came first. When his father died in 2011, he grew closer to his elderly mother, whom he cares for today. He dotes on the three grandchildren, although can’t be as active with them as he would like because of the pain.

One of his goals now is to relive his pain-free days and once again ride his Harley-Davidson motorcycle, which is owned by a niece.

Crisler lives with his mother, who will soon turn 90, in her home bordering Kennesaw Mountain National Battlefield Park. Without him, she could no longer stay there. They take care of each other.

“God kept me alive, knowing what was going to happen when my dad passed away. This let my Mom stay in her house,” he said. “God kept me around for some reason, and it wasn’t because I lived this great, honorable life. I didn’t. But I’m here today. God had a plan.”