Mesothelioma Survivor Cherishes Time Outdoors After Aggressive Surgery

Written by Tim Povtak | Edited by Walter Pacheco | Last Update: 08/05/2025 | 7 Min Read

Kevin Sinyard, a mesothelioma survivor, was back on the boat in the Florida Keys, once again joining family for the lobster harvesting season they enjoy so much.

His role may have changed, but his enjoyment of the outing remains.

“Some of the things I used to do I’ll never do again. I’ve learned my limitations,” he said. “I’m not the diver I was anymore. The water could become my kryptonite. I’m the one on the boat now passing out the beer, tending the cooler. And we still have a really good time.”

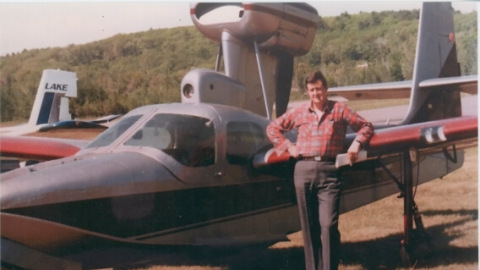

Sinyard, an avid outdoorsman, spent much of this last trip fishing, landing grouper, snapper and Key West grunts. He swam with the grandkids. He did most of the cooking. He rarely stopped smiling.

He was thrilled to be back in his environment, once again the jovial, talkative, fun-loving guy he was before pleural mesothelioma almost killed him.

Not bad for someone whose right lung was removed as part of the aggressive extrapleural pneumonectomy surgery he endured in 2014 after being diagnosed and told he had six months to live.

“What I’ve been through with mesothelioma I wouldn’t wish on my worst enemy. It’s a tough road to travel, a deadly disease, and very few make it out alive,” he said. “But I’m proof that you can survive and still live a really good life.”

Finding the Right Mesothelioma Specialist

Sinyard, 62, was fortunate to find thoracic surgeon Dr. Daniel Miller, a heralded mesothelioma specialist at Cancer Treatment Centers of America in Atlanta. The two bonded well, both believing the surgery risk was worth the reward.

Sinyard’s EPP surgery was intense. It removed the entire lung, the lining around it, two ribs and a major part of his diaphragm, which had to be rebuilt.

Most malignant mesothelioma specialists no longer attempt it today, preferring a safer surgical approach that preserves the lung but rarely achieves the same maximum tumor cell removal. Sinyard’s surgery was followed by equally aggressive chemotherapy and radiation regimens.

“I’ve been blessed. I found the best doctor out there – as good as it gets – and he told me, ‘I’ve got you, dude. You’re going to live, but you’re going to go through hell first,’” Sinyard said. “He gave me hope when I had none. Mesothelioma is not a death sentence. Well, it is, but it’s not.”

Aggressive Treatment Takes its Toll

The side effects of the multimodal treatment were debilitating at times. Sinyard dropped from 230 pounds to 180. He fought depression. He often saw no light at the end of the tunnel, wondering if he had made the right decision.

“You go through something like this, you have some dark, dark thoughts. I hurt that bad. When you face the devil, a crisis like this, your mind can go a lot of places, dark places,” he said. “All you think about is, you’re going to die, and how am I going to get through this.”

For almost two years after surgery, Sinyard rarely talked to others about his cancer journey. He stayed home a lot more. His outgoing personality changed dramatically.

He had spent most of his professional life as a steamfitter tradesman throughout the state of Georgia, installing, assembling and repairing industrial piping. He didn’t return many calls from long-time co-workers in the first year after surgery.

Support Group and Faith Were Critical

Fortunately, though, his support group of family and close friends never wavered, rallying around the man they had known and loved for many years in McDonough, Georgia.

His two grown sons, who were running the family business, and their wives were never far away. Wife Starla Sinyard rarely left his side.

Together, the couple adopted the biblical “Faith, Not Fear” logo as a rallying cry, putting it on armbands they distributed to everyone they knew. The two often prayed together.

“It took me a couple years to get back on my feet and be able to talk about what I’ve been through,” Sinyard said. “I had a strong woman behind me. You can’t make it through this without a real support group. She wouldn’t let me quit. When you’re going through chemo, it knocks you on your ass. But she got me back up every time.”

Sinyard also credits his Christian faith for pulling him through the post-surgery blues and allowing him to again become the man he was.

“If you don’t have faith in the good Lord, it would be so easy to go down the rabbit hole of gloom and doom and never get out,” he said. “The good Lord has taken care of me a long time, and he always will. I still like to cuss and drink and cut up and have fun. So, I know if he didn’t have a sense of humor, I wouldn’t be here today.”

While the median pleural mesothelioma survival rate is less than a year, those undergoing surgery have pushed their median to more than two years. Sinyard considers himself blessed to be a survivor moving closer to eight years now.

“I’m thankful for every day when I wake up,” he said. “I was scared, terrified, for a long time, but now I don’t worry. The Lord has a plan for me, and I’m thankful for that.”

Fun-Loving Outdoorsman Has Returned

Sinyard’s most serious health issue now is high blood pressure. He had his right hip replaced before mesothelioma struck. His right knee was rebuilt in recent years. He can joke now about his missing right lung and that side of his body.

“Now when I get in the water I can only swim to my right. I am missing everything there,” he said with a laugh. “I told my wife, if at some point they take my right nut, then just shoot me.”

He returns to see Miller every two years for a checkup and new CT scans. They still laugh about Sinyard’s dislike of traditional pain medication and a preference for taking shots of bourbon instead.

When his last checkup in May showed no signs of problems, he and his wife celebrated by embarking on a monthlong road trip. It included nights in Muscle Shoals, Alabama; Memphis, Tennessee; Little Rock, Arkansas; and Oklahoma, North Texas, Colorado, Arizona and Albuquerque, New Mexico.

He drove the whole way.

“We had a good time. We don’t sit around. We checked out a few breweries, distilleries,” he said. “We still like to travel and enjoy ourselves. And for that, I’m thankful.”

Sinyard still enjoys deer hunting with his sons, and now a grandson who also has developed a love for the outdoors. Although lobstering in the Florida Keys requires a more strenuous swim – which he avoids – he believes his one lung can handle the shallower water and easier catch of scallops next summer off the west coast of Florida. His left lung capacity has increased by 25%, partially compensating for the loss of the other one.

“You really don’t know what tomorrow will bring. I’ve made some concessions, but I haven’t stopped living,” Sinyard said. “I used to really like a good cigar, but I can’t smoke them anymore with one lung. So I just chew on them now.”