Meet the Group with Highest Mesothelioma Mortality Rate in the World

Awareness & ResearchWritten by Lorraine Kember | Edited By Walter Pacheco

The Karijini National Park in Western Australia is a natural wonder.

Sprawled over 193,000 square miles of the Hamersley Range deep in the heart of the Pilbara Region, the hauntingly beautiful landscape of mountain ridges, bottomless escarpments, spectacular gorges and cascading waterfalls is the traditional home of the Banyjima, Kurrama and Innawonga aboriginal people.

Their empathy and respect for the area comes from their vast knowledge of its land and water as well as the customs and traditions handed down from generation to generation.

The contemporary and archaeological significance of Karijini National Park to aboriginal people is evident in paintings on cave walls in numerous areas of the park.

Concerned more for what was on the land than beneath it, the aboriginal people of this area didn’t know that toxic asbestos lurked in the Wittenoom Gorge until mining operations began in the mid-1940s.

The Colonial Sugar Refinery started blue asbestos mining operations at the site in 1943 and employed aboriginal men and women as pick miners.

Joining the thousands of Europeans who flocked to the Pilbara to take advantage of the mining boom, the aboriginal people didn’t know their world was about to be torn apart.

Because of their prolonged exposure to asbestos, the aboriginals have the highest mortality rate from malignant mesothelioma than any other group in the world.

Asbestos Exposure Rampant in Wittenoom Mine

Conditions at the mine were appalling. Spending long hours underground, the workers were issued simple picks and shovels to free seams of asbestos from solid rock.

The dust from this exercise constantly rose into the air and surrounded them like a cloud.

Sometimes it was so thick they could barely see their hands in front of their faces. The job of shoveling freed asbestos into jute bags usually fell to the aboriginals.

At no time were they offered masks to prevent inhaling the deadly fibers.

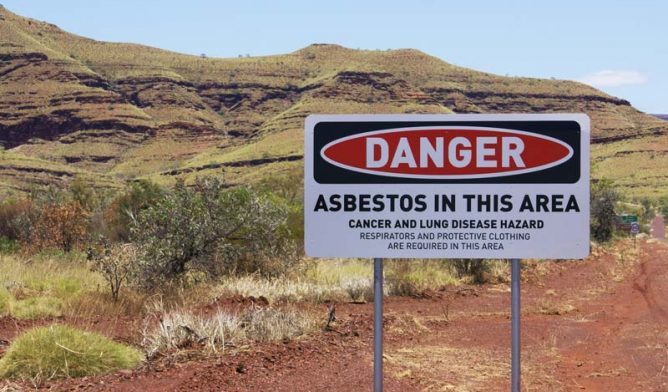

The end of a work day brought no relief. As the aboriginals made their way out of the dusty mine shafts, they were confronted with asbestos contamination as far as the eye could see.

Clouds of asbestos-laden dust blanketed the town. Asbestos tailings (residue of mined asbestos) were used to suppress dust and heat on road verges, backyards, school ovals, a local drive-in and the local race course.

Women and Children Also Exposed

Every aboriginal family took part in asbestos mining operations in Wittenoom in some way. Those who didn’t work in the mine loaded and unloaded bags of asbestos onto trucks used to transport the mineral to port of Roebourne, located roughly 125 miles north of the town.

The trucks were also a popular form of transport for aboriginal family members wanting to visit the port or other tribes in the area.

Perched high on the bagged asbestos, they were soon covered in dust that seeped easily out of the jute bags. Unaware of the danger, they enjoyed the drive and thought of it as an adventure.

The aboriginal children didn’t think anything of the contamination. They would regularly climb asbestos tailings and roll down the piles to cool pools of water.

Asbestos Exposure Continued After Mining Stopped

Colonial Sugar Refinery ceased asbestos mining in 1966. When the workers left, the aboriginals remained, along with 3 million tons of asbestos tailings spread across their land.

This group now has the highest mortality rate of mesothelioma in the world. Adding to the tragedy, many died when they were in their 40s.

The exact number of aboriginal deaths linked to asbestos cannot be determined because of lack of medical data.

However, it is known that thousands of people who lived and worked in Wittenoom died of mesothelioma or other asbestos-related diseases.

Tragically, this trend is likely to continue for a very long time.

The mounds of deadly asbestos tailings — so immense they can be seen from space — continue to contaminate the air, land and water of the area.

Wittenoom Gorge Elders Demand Tailings be Cleaned

What to do about the problem of asbestos in Karijini Park has plagued Australian officials for over 50 years.

But despite feasibility research regarding a cleanup of the region and reports that rain and erosion had significantly spread asbestos into the creeks that flow into the Fortescue River catchment, nothing was done.

In 2018, following the advice of Barrister John Gordon, who specializes in asbestos litigation, the Native Title Holders Corporation passed a resolution considering legal action against the local government.

Sadly, nothing has come of it.

“The State Government, in the interests of public health, recognizes the importance of resolving historic issues of asbestos contamination in the Wittenoom area,” officials said in a statement. “The Government is working through this complex issue to provide certainty to the community. We will continue to engage in discussions with the community and relevant stakeholders.”

The aboriginals believe the reason their demands have fallen on deaf ears is because of the millions of dollars it would cost to remove the asbestos from their land.

They are probably right, but what about the value of human life?

Surely the government should be doing whatever it takes to clean up the toxic mess responsible for so many aboriginal deaths.

How many more generations must suffer and die of mesothelioma before something is done?