Mesothelioma Loss Inspires Boston Marathon Runner

Melanie Cruse ran the grueling Boston Marathon last month with an inspiring breeze at her back, lifting her through each hill she climbed and every stride she took.

Her father, Duane Bunkowske, provided the silent wind in the sail.

Bunkowske died from peritoneal mesothelioma 17 days earlier, but not before making Cruse promise him she would run the race. He promised to be there.

“I felt him the entire race, and especially on the inclines when it got tough,” Cruse said after returning home to Rapid City, South Dakota.

“I’d talk to him, think about him, feel him there. It was pretty emotional. When I reached the top of Heartbreak Hill, I said thanks, Dad, we did it.”

Bunkowske instilled in his family an unfailing belief in excellence and the pursuit of individual goals, a conviction Cruse kept alive through the 26.2 miles.

Her race was a tribute to his life.

Honoring Her Father

Cruse finished in 3 hours, 26 minutes, 22 seconds. The 32-year-old mother of three ran with her father’s initials — D.N.B. — carved into a pendent strapped to her shoe.

She ran to honor him that day. He had purchased a plane ticket to Boston the day after she qualified, and she carried it onto the flight.

Melanie Cruse running the Boston Marathon.

He would have beamed watching his pride and joy reach the pinnacle of marathon running, a hobby she began at his suggestion after her first child was born, and after her years as a serious dancer and gymnast had passed.

Even when doctors told Bunkowske surgery was not an option and he would never make it to Boston to see his daughter run, he still promised her he’d be waiting at the finish line like always.

“He said you’ve got to run, no matter what,” Cruse said.

Bunkowske died the next day.

An Unlikely Victim

Mesothelioma was a stunning diagnosis for Bunkowske, his wife, Jill, and the rest of the family. He was 62 and had settled comfortably into an early and active retirement years earlier after a career in banking.

He was a former high school track and field state champion. As a college baseball player at South Dakota State University, he was good enough to earn a minor league tryout with the Oakland A’s. He played competitively into his ’50s, adding a serious golf game to his routine.

His favorite endeavor in retirement, though, was chasing and caring for the grandkids, now 2, 5 and 8, who lived a few minutes away. He made sure Cruse and her husband, Brandon Cruse, each had time to pursue their professional and personal lives.

Bunkowske loved being granddad while still young enough to play the games, teaching them baseball, tennis and football at an early age. He coached his own kids for years. Now, he was doing the same with the grandkids in the backyard.

He rarely missed their games. He would throw batting practice to Conor (the oldest grandchild), then take him golfing. He was already helping granddaughter Lilian with gymnastics. He often drove both to their practices. For him, it was not babysitting. It was grandfathering that he loved.

The End Came Quickly

It wasn’t until late in February, while vacationing with his wife in Mesa, Arizona, when Bunkowske started feeling odd. He thought it was heartburn or indigestion at first. It worsened quickly.

Early in March, they returned to Rapid City. Doctors began a battery of tests that revealed much more serious problems.

They sent him to the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, where he was diagnosed with peritoneal mesothelioma on March 22.

By March 30, he was gone.

“We had no indication whatsoever that he had something like this,” Jill Bunkowske said. “And even when he was diagnosed, he still thought, OK, I’ll get treated, maybe have surgery and then we’ll all go to Boston. It just happened so quickly, out of nowhere. The blessing is that we had 100 percent of him until the last two weeks. And he was so great.”

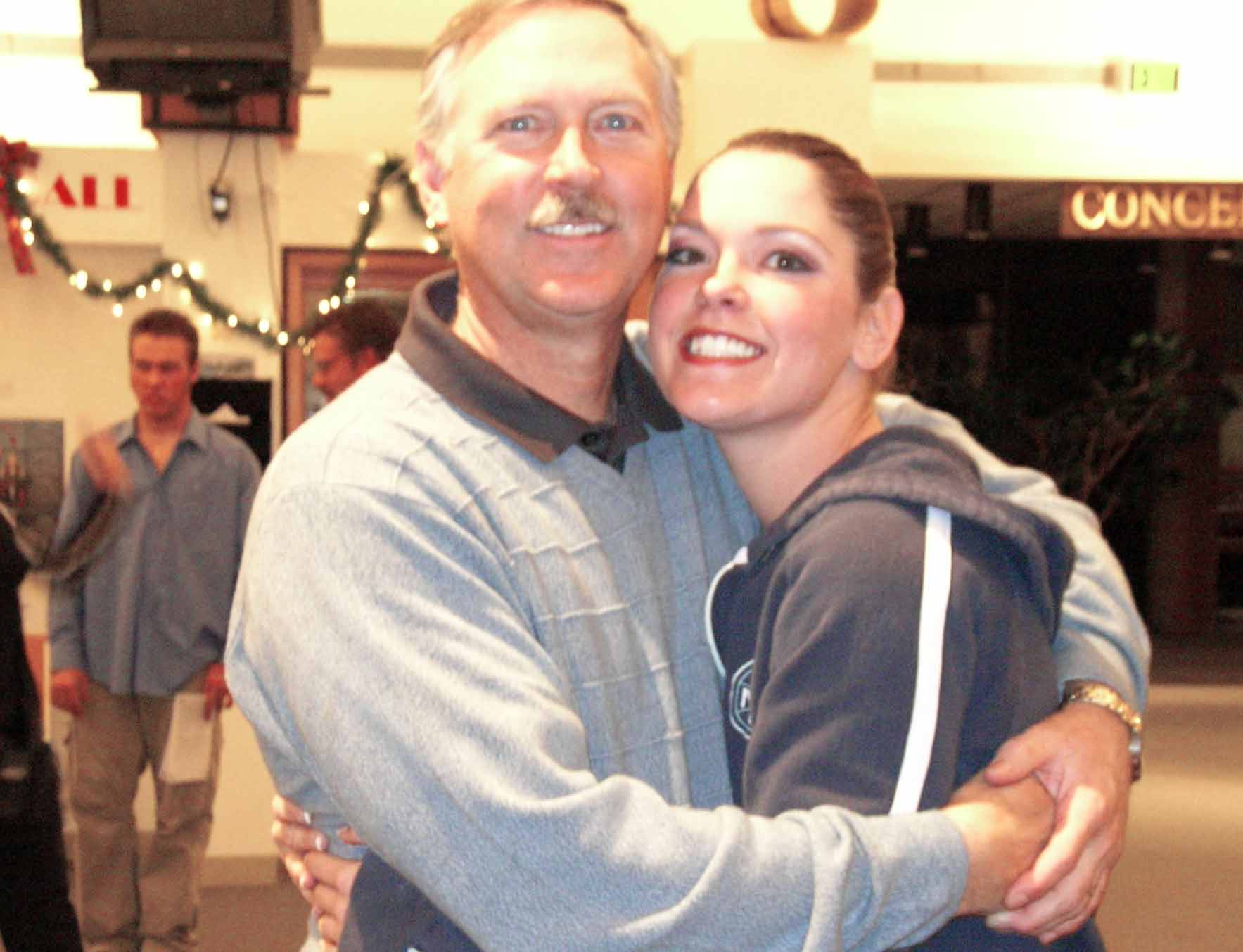

Melanie Cruse with her mother, Jill Bunkowske.

She does not think her husband’s mesothelioma was connected to asbestos exposure, the predominant cause of the disease. He spent his career in the banking business with no known exposure to toxic asbestos.

The Family Continues

Before Bunkowske retired, his wife and Cruse opened a fitness club together in Rapid City called Nucleo Fitness.

The company motto: “Have fun. Be fit. Feel amazing.” It epitomized the family.

The business gave Bunkowske more time with his grandkids. Cruse’s husband is an industrial engineer but moonlights on fall weekends as a college football official.

Two days after Bunkowske died, Conor was scheduled to leave for an overnight tennis camp several hours away. He had been hit hard by his grandfather’s passing. They were the closest. Like Cruse, though, Conor had absorbed the lessons Bunkowske had taught him.

Duane Bunkowske with his grandchildren.

Cruse and her husband gave Conor the option of skipping the camp to stay with the family as they grieved. He left for camp instead.

Jill Bunkowske recalled her grandson’s reasoning: “Why would I skip camp? Grandpa would have told me to get to camp and kick some butt.”

It was Conor’s reaction that cemented Cruse’s decision to still run the Boston Marathon. Her mother and husband went to support her.

“It was very healing for everyone, knowing that’s what Dad wanted,” Cruse said. “I know he was proud of me for reaching my goal of running Boston.”

Cruse’s mother and husband stood and watched at the 25-mile mark as she passed. They were wearing T-shirts with “Go Mel! Boston Marathon” printed on the front. Duane Bunkowske’s photo was on the back.

They stayed away from the finish line. That was reserved for Cruse and her father, who had made a promise to each other.

“He told me he would be at the finish line,” Cruse said. “And he was.”