Written by Daniel King | Edited By Walter Pacheco | Last Update: July 12, 2024

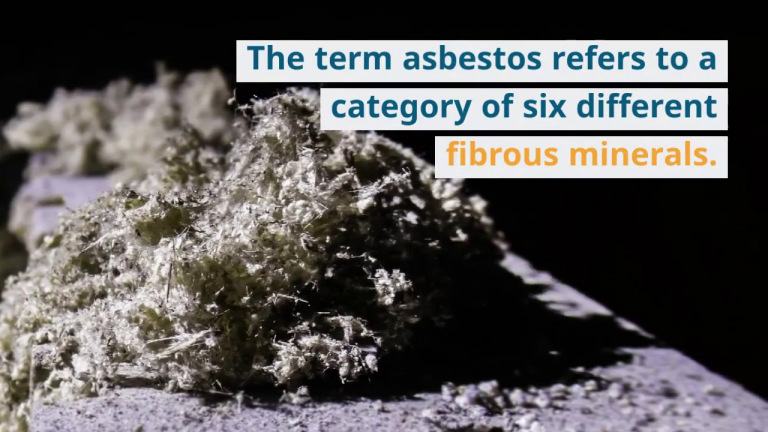

Why Was Asbestos Used?

The fireproofing properties of asbestos made it essential to many industries, such as the automobile, construction, manufacturing, power and chemical industries. The U.S. armed forces also used asbestos to prevent fires in every military branch. The primary intention of using asbestos was to protect workers, but many asbestos product manufacturers knew early on that working with the mineral caused harmful health effects.

Despite all the efforts to use asbestos safely, it remains a danger to human health, causing crippling diseases such as asbestosis, mesothelioma cancer, and lung cancer.

Asbestos in the Ancient World

Asbestos occurs naturally on every continent in the world. Archeologists uncovered asbestos fibers in debris dating back to the Stone Age, some 750,000 years ago. As early as 4000 B.C., asbestos’ long hair-like fibers were used for wicks in lamps and candles.

Between 2000-3000 B.C., embalmed bodies of Egyptian pharaohs were wrapped in asbestos cloth to protect the bodies from deterioration. In Finland, clay pots dating back to 2500 B.C. contained asbestos fibers, which were believed to strengthen the pots and make them resistant to fire. Around 456 B.C., Herodotus, the classical Greek historian, referred to using asbestos shrouds wrapped around the dead before their bodies were tossed onto the funeral pyre to prevent their ashes from being mixed with those of the fire itself.

Others believe the word’s origin can be traced back to a Latin idiom, amiantus, meaning unsoiled or unpolluted. The ancient Romans were said to have woven asbestos fibers into a cloth-like material sewn into tablecloths and napkins. These cloths were purportedly cleaned by throwing them into a blistering fire, from which they came out miraculously unharmed and essentially whiter than when they went in.

While Greeks and Romans exploited the unique properties of asbestos, they also documented its harmful effects on those who mined the silken material from ancient stone quarries. The Greek geographer Strabo noted a “sickness of the lungs” in enslaved people who wove asbestos into cloth. Roman historian, naturalist and philosopher Pliny the Elder wrote of the “disease of slaves.” He described the use of a thin membrane from the bladder of a goat or lamb used by the slave miners as an early respirator in an attempt to protect them from inhaling the harmful asbestos fibers as they labored.

Asbestos in the Middle Ages and Beyond

Around 755, King Charlemagne of France had a tablecloth made of asbestos to prevent it from burning during the accidental fires that frequently occurred during feasts and celebrations. Like the ancient Greeks, he also wrapped the bodies of his dead generals in asbestos shrouds. By the end of the first millennium, cremation cloths, mats and wicks for temple lamps were fashioned from chrysotile asbestos from Cyprus and tremolite asbestos from northern Italy.

In 1095, the French, German and Italian knights who fought in the First Crusade used a catapult, called a trebuchet, to fling flaming bags of pitch and tar wrapped in asbestos bags over city walls during their sieges. In 1280, Marco Polo wrote about clothing made by the Mongolians from a “fabric which would not burn.” Polo visited an asbestos mine in China to disprove the myth that asbestos came from the hair of a wooly lizard.

Chrysotile asbestos was mined during the reign of Peter the Great, Russia’s tsar, from 1682 to 1725. Benjamin Franklin brought to England a purse made of fireproof asbestos, now part of London’s Natural History Museum collection, during his first visit there as a young man in 1725. Paper made from asbestos was discovered in Italy in the early 1700s. By the 1800s, the Italian government utilized asbestos fibers in its banknotes. The Parisian Fire Brigade wore jackets and helmets made from asbestos in the mid-1850s.

Commercialization of Asbestos

Asbestos manufacturing was not a flourishing industry until the late 1800s when the start of the Industrial Revolution helped sustain its strong and steady growth. That’s when asbestos’s practical and commercial uses became widespread, with its myriad applications. As the mining and manufacturing of asbestos exploded, so did its dangerous health effects on those who mined and refined the mineral and those who worked with it.

Asbestos’ resistance to chemicals, heat, water and electricity made it an excellent insulator for the steam engines, turbines, boilers, ovens and electrical generators that powered the Industrial Revolution. Its malleable properties made it an important building, binding and strengthening commodity.

Asbestos Mining Around the Globe

In the early part of the 19th century, crocidolite (blue asbestos) had already been found in Free State, Africa. In 1876, chrysotile (white asbestos) was discovered in the Thetford Township, in southeastern Quebec. Shortly afterward, Canadians established the world’s first commercial asbestos mines. They joined Russia in excavating the soft, fibrous form of the mineral, which is found in more than 95 percent of all asbestos products.

The early 1870s also saw the founding of large asbestos industries in Scotland, Germany and England. Italy had been mining tremolite asbestos for decades. Australians began mining asbestos in Jones Creek, New South Wales, in the 1880s. By the early 1900s, anthophyllite asbestos was mined in Finland. Amosite (brown asbestos) was discovered in Transvaal, South Africa. Chrysotile from the mines of Swaziland and Zimbabwe was mined and marketed worldwide.

Asbestos Production Increases

Before the late 1800s, asbestos mining was not mechanized. The heavy work of chipping away rock and extracting the asbestos for further processing was performed manually. Horses and drays were utilized to transport the mined product. However, once the commercial applications for asbestos were realized and demand grew, asbestos mining became industrialized. Steam-driven machinery and new mining methods multiplied its manpower.

By the early 1900s, asbestos production had grown worldwide to more than 30,000 tons annually. Children and women were added to the asbestos industry workforce, preparing, carding and spinning the raw fibers, while men toiled in the mines.

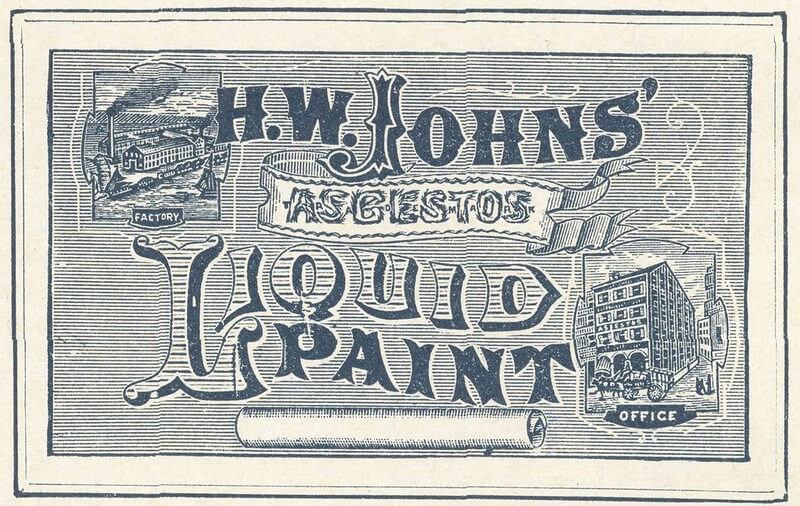

The uses of asbestos expanded just as rapidly as its manufacture. Henry Ward Johns in 1858 founded the H.W. Johns Manufacturing Company in lower Manhattan when he was 21. He sold new, fireproof roofing material made of burlap, asbestos, tar and other ingredients. The anthophyllite asbestos came from a quarry in nearby Staten Island. For the next 40 years, before he died from “dust phthisis pneumonitis,” believed to be asbestosis, Johns greatly expanded the number of asbestos applications. His firm merged with the Manville Covering Company in 1901. Johns Manville became the most prominent manufacturing enterprise that used asbestos in the U.S.

In 1896, Ferodo, a British company, made the first asbestos brake linings for new horseless carriages. Three years later, in Germany, the first patent was issued for the manufacture of asbestos cement sheets. Klinger in Austria produced high-pressure asbestos gaskets in 1900. The first asbestos pipes were developed in Italy in 1913.

Mining in the U.S. spiked in the 1960s and 1970s, with dozens of operations on the East Coast and in California. The King City Asbestos Company (KCAC) mine in west-central California was the last active asbestos mine in the U.S., closing in 2002.

Documenting the Hazardous Effects of Asbestos

As early as 1897, an Austrian doctor attributed pulmonary troubles in one of his patients to the inhalation of asbestos dust. An 1898 report regarding the asbestos manufacturing process in England, where factories had been routinely inspected since 1833 to protect the health and safety of workers, cited “widespread damage and injury of the lungs, due to the dusty surrounding of the asbestos mill.”

In 1906, the first documented death of an asbestos worker from pulmonary failure was recorded by Dr. Montague Murray at London’s Charring Cross Hospital. The autopsy of the 33-year-old victim revealed large amounts of asbestos fibers in his lungs. Reports of worker deaths from “fibrosis” in asbestos plants in Italy and France echoed studies in the U.S. that suggested that asbestos workers were dying unnaturally young. As early as 1908, insurance companies in the U.S. and Canada began decreasing coverage and benefits while increasing premiums for workers employed in the asbestos industry.

Get help paying for mesothelioma treatment by accessing trust funds, grants and other options.

Get Help NowAsbestos Industry: Once an Unstoppable Engine

Despite consistent health warnings, asbestos mining and manufacturing was an engine that could not be stopped. World production in 1910 exceeded 109,000 metric tons, more than three times the total in 1900.

In the United States, increased consumption stemmed from the population’s growing demand for cost-effective, mass-produced construction materials, and asbestos products filled that need. The U.S. quickly became the world leader in asbestos usage, with neighboring Canada furnishing a steady supply. The onset of World War I, followed by the Great Depression, temporarily slowed the asbestos industry’s exponential growth. The start of World War II revived that growth.

While mining and manufacturing during WWII declined in many asbestos-producing countries, Canada, South Africa, and the U.S. could supply much of America’s increasing wartime mineral needs. By 1942, U.S. asbestos consumption had risen to about 60 percent of world production, up from 37 percent in 1937. Heavy use of asbestos by the U.S. military eventually led to high rates of mesothelioma in veterans.

Asbestos in Common Products

Asbestos became an ingredient in several everyday products used in construction and automobiles. Several factors contributed to a rise in the production and consumption of asbestos products, especially in the United States. A brisk rise in the domestic construction industry increased demand for a growing number of asbestos-based products.

- Asbestos cement

- Asbestos insulation for electric wiring

- Asbestos roofing and flooring compounds

- Thermal insulation for homes and offices

- Automotive and airplane clutches

- Asbestos millboard and paper for electrical panels

- Heat and acid-resistant gaskets and packing materials

- Fillers and reinforcement for plasters, caulking compounds and paints

- Spray-on, fire-retardant coating for steel girders in buildings

- Car, truck and airplane brake pads and linings, seals and gaskets

As cars became a common element of the American landscape, so did new, more durable roads. Some roads built in the U.S. between the 1930s and 1950s contained asbestos-laced asphalt.

Houses that were built before the 1980s have a high chance of containing asbestos in construction materials, and so firefighters and construction workers that deal with damaged household materials often find themselves exposed to asbestos in high amounts.

Modern Demand for Asbestos

Global demand for asbestos increased as economies and countries struggled to rebuild after the war. U.S. consumption also grew in the post-war years because of a massive expansion of the American economy and the sustained construction of military hardware during the Cold War.

U.S. consumption of asbestos peaked in 1973 at 804,000 tons. The peak world demand for asbestos was around 1977. Some 25 countries produced almost 4.8 million metric tons per year, and 85 countries made thousands of asbestos products.

However, by the late 1970s, a dramatic decline began in the use of asbestos throughout the industrialized nations. The public was starting to understand the connection between asbestos exposure and debilitating lung diseases.

Organized labor and trade unions demanded safer and healthier working conditions, and liability claims against major asbestos manufacturers caused many of them to make and market asbestos substitutes.

By 2003, new environmental regulations and consumer demand helped push for full or partial bans on the use of asbestos in 17 countries:

- Argentina

- Austria

- Australia

- Belgium

- Chile

- Denmark

- Finland

- France

- Germany

- Italy

- Netherlands

- Norway

- Poland

- Sweden

- Switzerland

- Saudi Arabia

- United Kingdom

In 2005, asbestos was banned throughout the European Union. In recent years, many of the world’s emerging economies have embraced the use of asbestos as eagerly as more developed nations did for much of the last century.

Asbestos Ban in the U.S.

In March 2024, the Biden administration officially finalized plans to ban chrysotile asbestos. The toxic mineral, also known as white asbestos, continues to be imported into the U.S., mainly used in the chloralkali industry. The new ban allows companies up to 12 years to phase out the product from the manufacturing process. This ban doesn’t apply to all types of asbestos.

The last U.S. asbestos mine closed in 2002, ending more than a century of the country’s asbestos production. Although the United States has always been a significant importer of asbestos, historically providing only a tiny percentage of the world’s supply, it was always the world’s largest consumer.

This Page Contains 6 Cited Articles

The sources on all content featured in The Mesothelioma Center at Asbestos.com include medical and scientific studies, peer-reviewed studies and other research documents from reputable organizations.

- Davenport, C. (2024, March 18). U.S. Bans the Last Type of Asbestos Still in Use. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2024/03/18/climate/biden-administration-bans-asbestos.html

- U.S. EPA. (2020, December 30). EPA Actions to Protect the Public from Exposure to Asbestos. Retrieved from https://www.epa.gov/asbestos/epa-actions-protect-public-exposure-asbestos

- USGS. (2006). Worldwide asbestos supply and consumption trends from 1900 through 2003. Retrieved from https://pubs.usgs.gov/circ/2006/1298/c1298.pdf

- Webster, P. (2006). White Dust Black Death: The Tragedy of Asbestos Mining at Baryulgil. Trafford Publishing.

- Boslaugh, S. (2008). Encyclopedia of Epidemiology. Sage Publications, Inc.

- Schneider, A., & McCumbe, D. (2004). An Air That Kills. G.P. Putnam's Sons: New York.

-

Current Version

-

July 12, 2024Written ByDaniel KingEdited ByWalter Pacheco